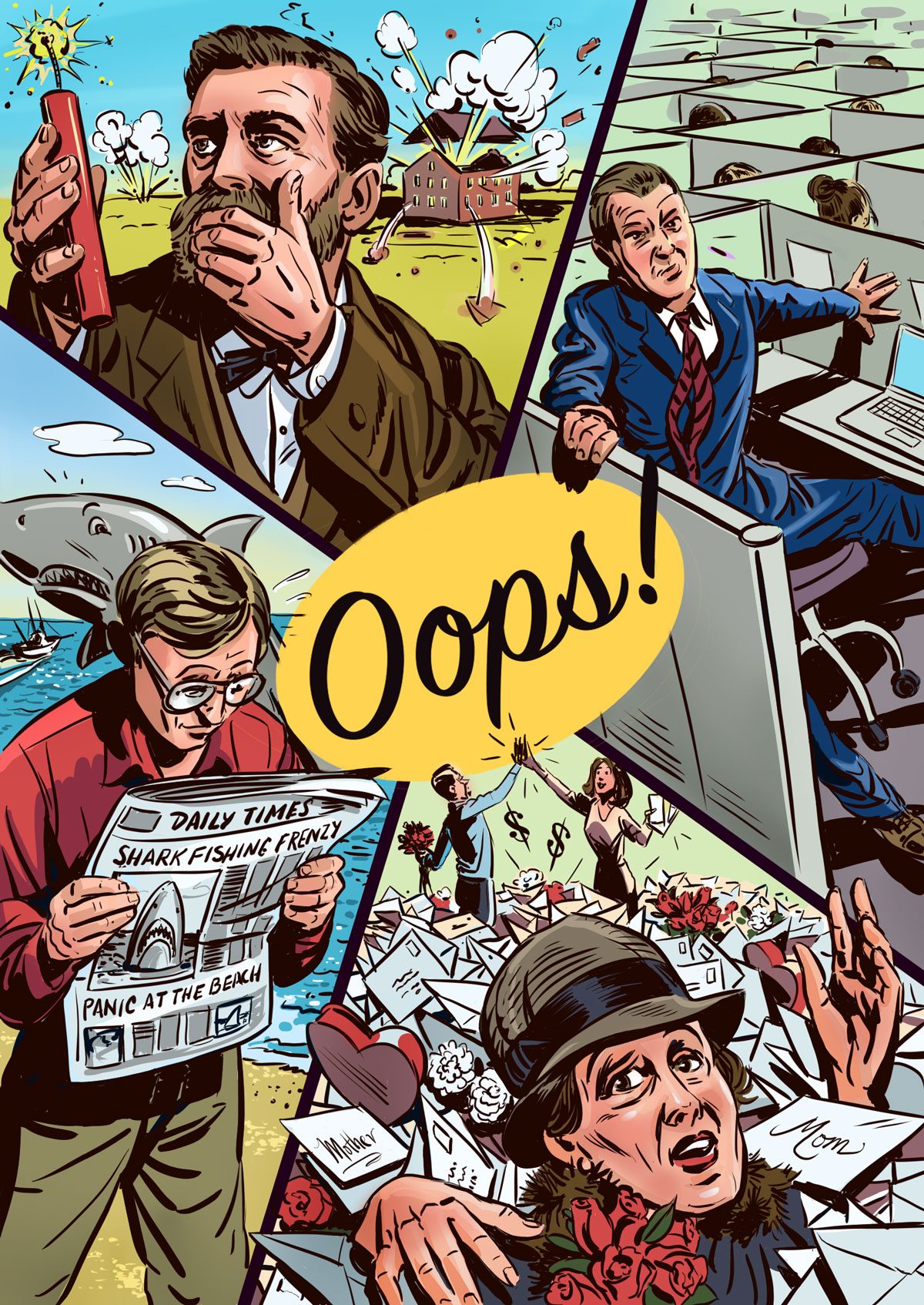

Some of the greatest minds in history went to their graves lamenting their most influential work. Like these eight groundbreakers ...

8 Genius Inventors Who Regretted Their Popular Inventions

You’ve probably heard of the brilliant minds behind some of today’s most groundbreaking inventions—think the light bulb, the telephone and the World Wide Web. But did you know that not every inventor was thrilled with how their creation turned out?

In fact, some of history’s most ingenious minds ended up deeply regretting the important inventions that made them famous. If curious to know who, we’re diving into the fascinating stories of both famous and lesser-known inventors who gave us some of the most impactful technologies and tools of our time, only to later wish they hadn’t. From weapons of war to addictive tech, these are the creations that sparked innovation and regret.

Read on to uncover the surprising reasons why innovation doesn’t always equal satisfaction—and how some world-changing inventions left their inventors haunted by their own genius.

Get Reader’s Digest’s Read Up newsletter for more fun facts, humor, cleaning, travel and tech all week long.

The inventor of dynamite

Alfred Nobel, a Swedish chemist and inventor, made his fortune as a young man developing nitroglycerin-based explosives for use in mining and engineering. He patented the blasting cap, or detonator, which allowed explosives to be triggered from safe distances. And then in 1867, he developed something that made nitroglycerin easier to use, store and carry anywhere from caves to bank vaults.

Nobel’s miraculous invention was dynamite, and it became a huge hit among miners, robbers and countless cartoon characters. Unfortunately, something happened that Nobel didn’t expect: His little boom stick made an even bigger splash among the world’s growing armies. Dynamite made its first wartime appearance during the Franco-Prussian War in 1870. And by the time the Spanish-American War came along in 1898, soldiers were shooting horrific weapons called dynamite guns at each other.

Nobel was so hurt by his reputation as a “merchant of death” that he set aside the bulk of his fortune to finance annual prizes for “those who, during the preceding year, have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind.” These awards are the Nobel Prizes, the highest and most sought-after academic honors in the world, and they probably would not exist had Alfred Nobel not dedicated so much of his life to explosions. That said, we imagine that Alfred Nobel might have regretted how some of his honorees used their brilliance to build ever-bigger explosives, such as the 31 Nobel Prize winners who worked on the Manhattan Project, which created an even larger boom stick—the first atomic bomb.

The designer of the office cubicle

Robert Propst was an American innovator whose inventions included heart pumps, farming equipment, hospital beds, children’s playgrounds and more than a hundred others. His most famous creation, however, is so universally despised that, in 2006, Propst described its widespread use as “monolithic insanity” on CNN Money.

Why was Propst so angry over something that made him famous? We’re guessing it’s because he did not like being credited as the man who gave the world the office cubicle. To be clear, Propst did not envision a future where countless people were stuffed into tiny pens like cattle. Quite the contrary: What we now call cubicles began as the Action Office, a furniture series that Propst developed for office furnisher Herman Miller. The Action Office was intended to make the workplace healthier and more productive by increasing physical activity and blood flow, including varying desk levels to enable people to work standing up part of the time.

“Walls could be removed to encourage physical interaction and productive conversation. Even the act of physically moving this stuff around for customization was considered a boon for employees,” reports IEEE Spectrum, a tech and engineering website. Unfortunately, these “movable walls” mostly remained stationary, making Propst’s creation an inexpensive incentive for business owners to, instead, cram more employees into smaller pens without having to hire construction crews to build walls around them.

As a result, Propst’s creation became a modern monster: a corporate prison that employees hated and that was later villainized in films like Fight Club and Office Space. “Not all organizations are intelligent and progressive,” he later said when interviewed by Metropolis magazine. “Lots are run by crass people. They make little, bitty cubicles and stuff people in them. Barren, rathole places.”

And that’s why we hate Mondays.

The founder of Mother’s Day

In the early 20th century, a little-known woman named Anna Marie Jarvis was animated by a noble cause. It centered around the mother she loved, a social activist in West Virginia who campaigned against childhood diseases and cared for soldiers on both sides during the American Civil War. When her mother died in 1905, Jarvis hoped to fulfill her late mother’s wish to establish “a memorial mothers day” to commemorate all mothers for their “matchless service” to humanity. And since her mother had been an advertising editor with Fidelity Mutual Life Insurance Co., Jarvis knew how to get this done: by sending out lots of letters.

Jarvis turned her mom’s dream into reality by organizing the world’s first Mother’s Day at Andrews Methodist Episcopal Church in Grafton, West Virginia, in 1908. She became the national spokesperson for the holiday and associated it with white carnations, her mother’s favorite flower because carnations don’t drop their petals. Instead, Jarvis explained, the flower “hugs them to its heart as it dies, and so, too, mothers hug their children to their hearts, their mother love never dying.”

Through a determined campaign of letter writing and lobbying, Jarvis convinced almost every state and eventually President Woodrow Wilson to recognize the holiday, and Wilson declared it a national observance in 1914. Unfortunately, things went downhill soon after that. Jarvis was infuriated that so many people were profiting from her holiday through chocolates, cards and Mother’s Day sales on products that today include SUVs and spa packages. She’s been quoted as complaining, “A printed card means nothing except that you are too lazy to write to the woman who has done more for you than anyone in the world. And candy! You take a box to Mother—and then eat most of it yourself. A pretty sentiment.” Ouch.

The unhappy activist protested the holiday and even spent time in jail for interrupting a 1932 rally of the American War Mothers, as the group sold carnations. By the 1940s, her attempts to formally rescind the holiday by going door to door to collect signatures were interrupted when she was committed to a mental institution. Jarvis spent the last years of her life there and told a reporter that she was sorry she ever started Mother’s Day.

Oh, and then there’s this: Her stay at Marshall Square Sanitarium may not entirely have been for her health. According to Olive Ricketts, director of the Anna Jarvis Birthplace Museum in Grafton, West Virginia, “Card and florist people paid the bill to keep her there.”

The author of Jaws

Jaws was a bestselling novel that became one of the most influential films in history. In 1975, a little-known director named Steven Spielberg turned the book’s title character, a great white shark, into cinema’s biggest monster since King Kong. The movie became the highest-grossing film in history at the time, the book sold nearly 20 million copies, and author/screenwriter Peter Benchley became a household name both for his thrilling storytelling and for accidentally causing a fishing frenzy that played a part in decimating the shark population.

That’s right. By the time Jaws became a franchise that not even Michael Caine could sink 12 years later in Jaws: The Revenge, the global population of several types of sharks was teetering toward extinction. The effect was so traumatic for Benchley that the poor guy dedicated the rest of his life to ocean conservation and even told the London Daily Express in 2006: “Knowing what I know now, I could never write that book today.”

Even Spielberg lamented the negative impact his film had on nature and on “the feeding frenzy of crazy sport fishermen” after Jaws premiered, he told the BBC. As for Benchley, he was driven to make amends by campaigning against the overfishing of sharks while also making documentaries that encouraged marine conservation.

The one thing he may not have regretted was ignoring his father’s suggested title for the book: What’s That Noshin’ on My Laig?

The inventor ofthe pop-up ad

Some creations are so disastrous that the whole world deserves an apology for them, be they the Ford Pinto, cancer-causing pollutants or that awful final season of Game of Thrones. But every now and then, something is so obnoxious that even its inventor becomes fed up with it. That’s why Ethan Zuckerman, the inventor of the pop-up ad, issued an apology to everybody on the internet.

Zuckerman told Forbes that many problems on the internet are “a direct, if unintentional, consequence of choosing advertising as the default model to support online content and services.” That’s a pretty broad blanket statement, but Zuckerman is an undisputed expert on online advertising.

“I wrote the code to launch the window and run an ad in it,” he said. If you ever used the internet and saw an advertisement appear out of nowhere atop of what you were reading, you have Ethan Zuckerman to curse for that. And if your computer ever slowed down or crashed because it was cluttered with ads appearing faster than you could close them, again, curse Zuckerman.

Zuckerman eventually acknowledged that he never intended this ad strategy to be so disruptive. “I’m sorry. Our intentions were good.”

The champion of a killing machine

In 1789, a French physician named Joseph-Ignace Guillotin proposed developing a machine that could make executions quicker and less painful—and by this reasoning, more humane. It was an honorable idea, for Dr. Guillotin detested capital punishment.

As you probably have guessed, Dr. Guillotin’s “machine” was the one widely used during the French Revolution to chop off people’s heads as quickly as Earth’s gravity allowed. The good doctor thought he was doing humanity a favor. But as guillotining prisoners became more frequent during the French Revolution’s Reign of Terror—more than 1,000 people met their fate that way—he was particularly horrified to learn in 1795 that the severed heads of guillotined prisoners still lived for several seconds. The proud humanitarian’s good intentions instead became, as one contemporary put it, “a terrible torture!”

Oh, and the worst part: Dr. Guillotin didn’t even invent what he had called, in his initial proposal, “my machine.” It was designed by a French surgeon and a German harpsichord maker. Dr. Guillotin had simply wanted a less painful form of execution. Oops.

“The godfather of AI”

In 2024, Geoffrey Hinton, PhD, was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for his “foundational discoveries and inventions that enable machine learning with artificial neural networks.” What is “machine learning”? It’s the field of study where computers adapt to new information the same way humans do: through experience and more data. This is why Hinton is sometimes called the godfather of AI (artificial intelligence), the groundbreaking technology now found in everything from medical diagnoses and spellcheckers to some vacuum cleaners.

But despite AI’s many positive uses, not to mention his own involvement in its development, Hinton has repeatedly stressed that AI technology is fast becoming an “existential threat” to humanity. “It’s conceivable that this kind of advanced intelligence could just take over.” What does the good doctor mean by “just take over”? “It would mean the end of people,” he explains. For those of us with plans in the near future, that’s a bit of a bummer.

So what could possibly go wrong? AI, either on its own or steered by bad actors, could commandeer our satellites, computers, militaries or even things as abstract as human interactions, art and decision-making. Naturally, this doesn’t mean an AI takeover of the planet is sure to happen. But, Hinton warned in Popular Science, humanity has “no experience with what it’s like to have things smarter than us.”

The creator of Sherlock Holmes

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was a multitalented man whose tales of The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes are among the most iconic and universally recognizable works of English literature. Holmes epitomized deductive reasoning in popular imagination and influenced later heroes like Batman, Nancy Drew, Harry Potter and Dr. House. However, the character’s initial popularity contributed to Doyle’s eventual dislike of Holmes, whom the author felt hurt his reputation as a writer and distracted him from projects he was more interested in writing, such as historical fiction.

According to the knight himself, “I’ve written a good deal more about Holmes than I ever intended to do. But my hand has been rather forced by kind friends who continually wanted to know more. And so it is that this monstrous growth has come out of a comparatively small seed.” Indeed, Holmes had become such a nuisance that his creator began exploring ways to bury him in more than pages.

Doyle eventually killed Holmes in the somewhat cheekily titled The Final Problem, but an American publisher with deep pockets persuaded Doyle to resurrect the character. “Arthur must have hated himself” for doing this, historian Lucy Worsley observed, “and he would have hated the fact that today, 93 years after his death, his historical novels lie unread, while his ‘cheap’—but beloved—detective lives forever on our screens.”

Why trust us

At Reader’s Digest, we’re committed to producing high-quality content by writers with expertise and experience in their field in consultation with relevant, qualified experts. We rely on reputable primary sources, including government and professional organizations and academic institutions as well as our writers’ personal experiences where appropriate. We verify all facts and data, back them with credible sourcing and revisit them over time to ensure they remain accurate and up to date. Read more about our team, our contributors and our editorial policies.

Sources:

- The Nobel Prize: “Alfred Nobel’s life and work”

- Pin-Up: “Inventor Robert Propst and the History of the Modern Cubicle”

- Kids Britannica: “Anna Jarvis”

- Britannica: “Jaws”

- History.com: “8 Things You May Not Know About the Guillotine”

- Britannica: “Geoffrey Hinton”

- Britannica: “Arthur Conan Doyle”

- Popular Science: “‘Godfather of AI’ wins Nobel Prize for work he fears threatens humanity”