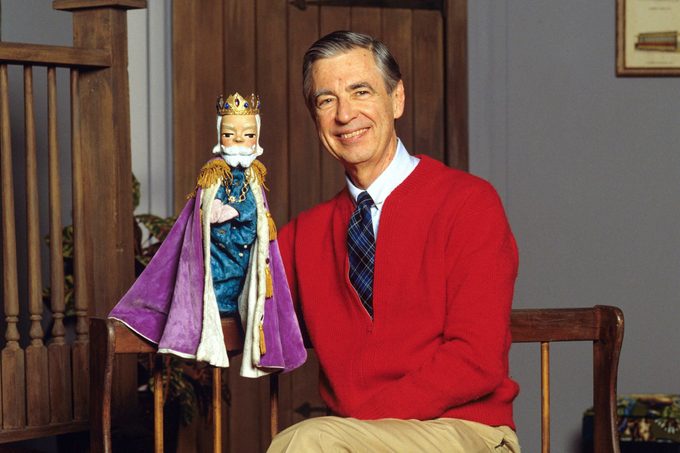

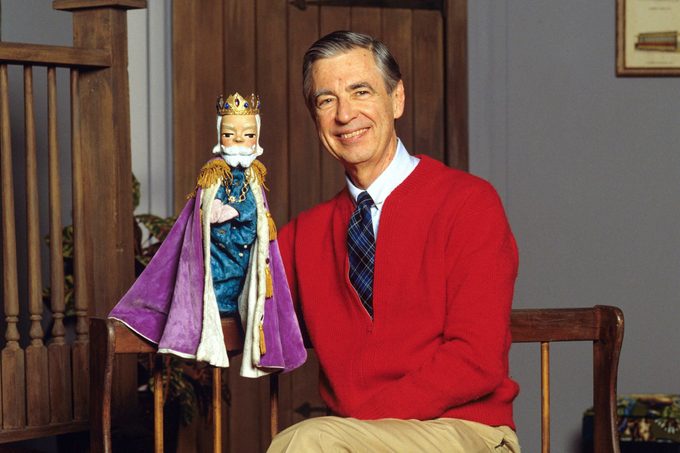

Before Fred Rogers became a beloved children's television host, he overcame a difficult childhood that enabled him to show deep empathy toward others

The Sad Story Behind Mr. Rogers’s Hallmark Empathy

Fred Rogers, the beloved host of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood from 1968 to 2001, remains iconic for his red cardigans, sneakers, love of children and, above all, his lessons in kindness. But behind that gentle demeanor was a man who overcame a difficult and lonely childhood before finding his true calling. More than 20 years after his death in 2003 at age 74, it’s time to learn more about his past—and get fresh insight to help answer the question of who is Mr. Rogers. Keep reading for a deeper look at this much loved American figure.

Get Reader’s Digest’s Read Up newsletter for more curiosities, humor, cleaning, travel, tech and fun facts all week long

Did Mr. Rogers have a challenging childhood?

Yes, he did. An only child until a sister was adopted into the family when he was 11, Rogers was overweight, shy and sheltered. He also suffered from severe asthma, scarlet fever and “every imaginable childhood disease,” as he put it in a 2002 interview. Such circumstances made it difficult for Rogers to fit in at his elementary school in industrial Latrobe, Pennsylvania, about an hour outside of Pittsburgh.

“I felt I had no friends,” Rogers said in a speech he gave at Saint Vincent College in April 1995. In the same speech, Rogers tells of a time when he was walking home from school and a “whole group of boys” began following him. As he walked the 11 blocks to his house, the boys began taunting him, then chased after him as he ran away, shouting all the while: “Freddy, hey fat Freddy! We’re going to get you, Freddy!”

This was not the only time Rogers was bullied. One of his childhood classmates, Rudy Prohaska, remembers children at school “calling him names” and “bullying Fred,” according to Rogers’s biographer, Maxwell King, in The Good Neighbor: The Life and Work of Fred Rogers. “There were a lot of people in school who irritated me by the way they treated him,” Prohaska said. “I couldn’t take the name-calling and all that.”

Such experiences left Rogers traumatized. “I cried to myself whenever I was alone,” he said in the Saint Vincent College speech.

“It seems that Fred’s greatest adversity was loneliness,” Emily Uhrin, an archivist and researcher at the Fred Rogers Center in Latrobe, tells Reader’s Digest. “He was overweight and shy and sometimes felt that people could not look beyond those things.”

The solitude and bullying made for a difficult childhood, but it also gave Rogers a deep well of understanding toward others. He said in the Saint Vincent College speech that the negative experiences of his childhood made him “[seek] out stories of other people who were poor in spirit, and I felt for them.”

Who helped Mr. Rogers come out of his shell?

To understand who is Mr. Rogers, it’s important to learn about the people who saw past his awkwardness. Per Uhrin, one time Rogers wanted to climb a stone wall at his grandfather’s farm but his mother and grandmother wouldn’t let him because they didn’t want him to get hurt. His grandfather stepped in and encouraged his grandson to climb the wall “because he needed to learn to do things for himself.”

Another person who advocated on Rogers’s behalf was one of his high school classmates, Jim Stumbaugh. “Jim was popular, and Fred wasn’t,” Uhrin explains. But Rogers’s social standing improved when Stumbaugh became injured in a football game and Rogers delivered his homework to him at the hospital. Stumbaugh got to know a different side of Rogers through their interactions. Later, when he returned to school after his injury, Stumbaugh took Rogers under his wing. “Fred credited Jim with giving him the confidence to have a good high school experience,” Uhrin says.

How did Mr. Rogers channel adversity into strength?

As Stumbaugh looked out for Rogers, Rogers looked out for others. “Fred Rogers was intentional in all that he did,” Roberta Schomburg, executive director at the Fred Rogers Center, tells Reader’s Digest. Journalist Tom Junod, one of Rogers’s friends and the inspiration behind the 2019 movie A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood, observed something similar in his interactions. “When Fred asked you a question, he wanted to know the answer,” Junod says. “He made kindness a practice, not just something he talked about.”

Junod witnessed Rogers’s hallmark empathy firsthand and tells Reader’s Digest he considers it “one of the great honors and gifts of my life” that he was on the receiving end of Rogers’s kindness. “To be one of those people that he prayed for, one of those people that he cared for; I’ll never really understand how it happened, but I’m really glad that it did,” he says.

Junod, who first met Rogers when he profiled him for Esquire in 1998, adds that he felt Rogers’s love and concern in the form of countless letters, emails and phone calls. “Fred had a tuning fork from his own experiences that gave him insight into what other people needed,” Junod continues. “What sets Fred apart is that he wasn’t just a nice guy who helped out people with whatever they needed,” Junod explains. “He was also a true authority figure who, in his own way, was a very powerful human being, and he used that power to do good.”

Why is Mr. Rogers still so important?

Rogers is credited with teaching generations of children to be kind and to act with empathy. And to think: Rogers’s compassion, understanding and everything he came to mean to so many people around the world may never have been if not for a difficult and lonely childhood that shaped a boy into the man he became.

That’s why David Newell, a longtime friend of Rogers’s who played Mr. McFeely on Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, said it best in the acclaimed 2018 documentary Won’t You Be My Neighbor?: “I’ve often wondered, if there hadn’t been a ‘fat Freddy,’ would there have been a Mr. Rogers?”

About the experts

|

Why trust us

At Reader’s Digest, we’re committed to producing high-quality content by writers with expertise and experience in their field in consultation with relevant, qualified experts. We rely on reputable primary sources, including government and professional organizations and academic institutions as well as our writers’ personal experiences where appropriate. We verify all facts and data, back them with credible sourcing and revisit them over time to ensure they remain accurate and up to date. Read more about our team, our contributors and our editorial policies.

Sources:

- Fresh Air: “Children’s TV Host Fred Rogers”

- Roberta Schomburg, professor of education at Carlow University in Pittsburgh and Fellow of the Fred Rogers Center for Early Learning and Children’s Media

- Emily Uhrin, archivist at the Fred Rogers Center for Early Learning and Children’s Media

- Tom Junod, writer of celebrity stories, features and personal essays for publications including Esquire, GQ, ESPN and The Atlantic

- The Good Neighbor: The Life and Work of Fred Rogers by Maxwell King